LIGO Station honors Downeast Maine's fleeting connection with one of the grandest achievements of modern science. In the 1980's the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Project identified this spot in Columbia near Schoodic Lake as a candidate site for their eastern U.S. gravitational wave detector.

The story begins in 1915, when Albert Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity, sparking a revolution in scientific thought that transformed our understanding of the Universe. Despite the theory's many successes, one of its strange predictions could not be immediately confirmed: that massive bodies in motion can send tiny ripples in the fabric of spacetime hurtling outward into the Universe at the speed of light. Because these "gravitational waves" were such a subtle effect, physicists initially doubted that they could ever be observed. But, thanks to the dogged efforts of a few hardy researchers and advancements in technology that Einstein could never have foreseen, these spectacularly tiny vibrations have now been recorded.

But where do you begin to look for these spectacularly tiny vibrations? The designers of LIGO knew that a gravitational wave detector called for a special site. It would have to be an exceptionally quiet place, far from sources of man-made and seismic noise. It would have to be on relatively flat and dry terrain, with plenty of wide open space on which to erect the detector's L-shaped pair of perfectly straight 4-kilometer-long laser interferometer tubes. Once built, the detector would require access to high-voltage power lines to drive the sophisticated lasers, electronics, cooling systems, and computers. The blueberry barrens near Schoodic Lake met all these criteria and seemed an eminently suitable fit. [See the 1985 introductory letter from the LIGO team to U.S. Representative Olympia Snowe.]

As part of the site evaluation process, the Archaeology Research Center of the University of Maine at Farmington conducted a field survey in 1987 to assess the impact of LIGO construction on archaeologically sensitive sites in the area. Although the survey did find traces of significant ancient human activity nearby — some dating back to the early Holocene era (9,000-7,000 BCE) — the researchers concluded that LIGO construction would pose no threat to these sites. ["Archaeological Phase I Survey and Phase II testing of the Laser Interferometer Gravity-Wave Observatory (LIGO)

Project in Columbia Twp, Washington Co. ME", Petersen and Heckenberger (1987); Maine Historic Preservation Commission document #2454]

Despite these promising indications, the National Science Foundation eventually selected an alternate site in Livingston, Louisiana for LIGO's eastern detector. (A site in Hanford, Washington was chosen for the western detector.) The project went forward, the detectors were built, and in 2016 LIGO announced that both had successfully recorded the first-ever gravitational waves, apparently generated from a distant pair of colliding black holes. With this dramatic discovery the last untested prediction of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity was confirmed and a door opened to an entirely new kind of deep-space astronomy.

Although the LIGO detector in Columbia was never built, this tranquil spot in the rolling blueberry barrens of rural Maine stands as an important landmark to the ingenuity of the human intellect, and a reminder of Maine's long history as a place for creators, thinkers, visionaries, and dreamers.

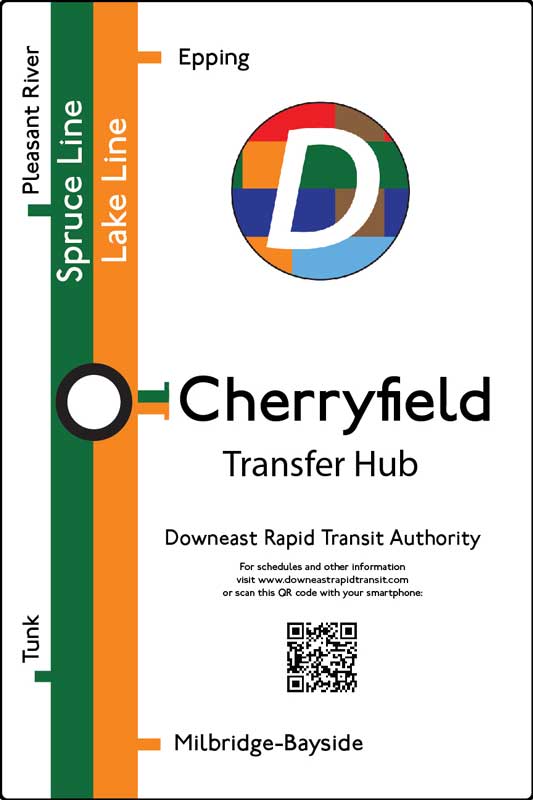

Station entrance: Off Webb District Road (near Baseline Rd.), Columbia. Near the Epping Baseline West survey marker, and stop #21 on the Maine Ice Age Trail.

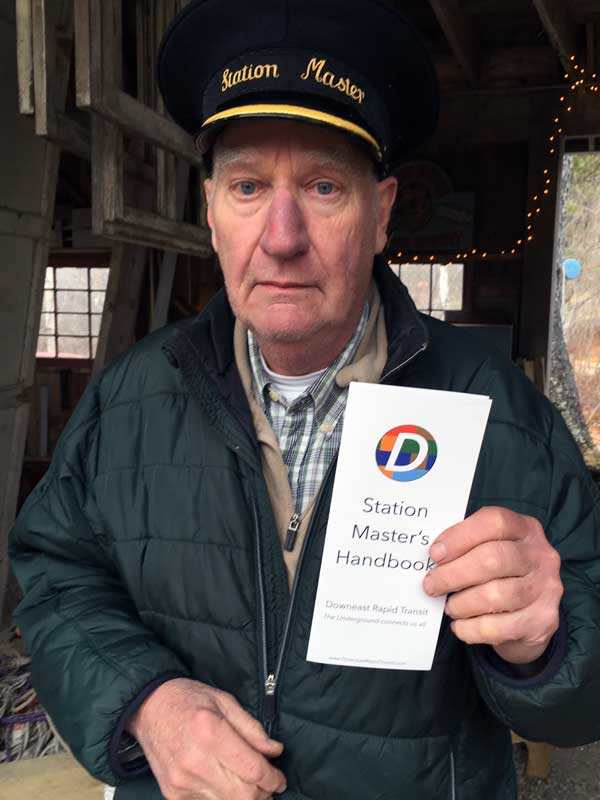

Stationmasters: Rainer Weiss (1932–2025) and Peter R. Saulson

We are experiencing delays on the

We are experiencing delays on the